|

|

|

|

PLEASE! If you see any mistakes, I'm 100% sure that I have wrongly identified some birds.

So please let me know on my guestbook at the bottom of the page

So please let me know on my guestbook at the bottom of the page

The Common Starling (Sturnus vulgaris), called Stare in Skåne, also known as the European starling, or in the British Isles just the starling, is a medium-sized passerine bird in the starling family, Sturnidae. It is about 20 cm long and has glossy black plumage with a metallic sheen, which is speckled with white at some times of year. The legs are pink and the bill is black in winter and yellow in summer; young birds have browner plumage than the adults. It is a noisy bird, especially in communal roosts and other gregarious situations, with an unmusical but varied song. Its gift for mimicry has been noted in literature including the Mabinogion and the works of Pliny the Elder and William Shakespeare. The Common Starling has about a dozen subspecies breeding in open habitats across its native range in temperate Europe and western Asia, and it has been introduced to Australia, New Zealand, Canada, United States, Mexico, Peru, Argentina, the Falkland Islands, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, South Africa and Fiji. This bird is resident in southern and western Europe and southwestern Asia, while northeastern populations migrate south and west in winter within the breeding range and also further south to Iberia and North Africa.  Common Starling / Stare ready to fly south

Bjuv, Sweden - 28 September 2019

Common Starling / Stare ready to fly south

Bjuv, Sweden - 28 September 2019

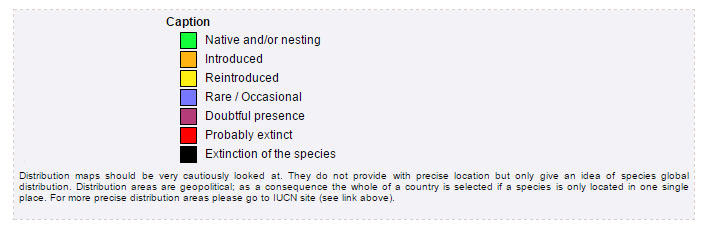

The Common Starling builds an untidy nest in a natural or artificial cavity in which four or five glossy, pale blue eggs are laid. These take two weeks to hatch and the young remain in the nest for another three weeks. There are normally one or two breeding attempts each year. This species is omnivorous, taking a wide range of invertebrates, as well as seeds and fruit. It is hunted by various mammals and birds of prey, and is host to a range of external and internal parasites. Large flocks typical of this species can be beneficial to agriculture by controlling invertebrate pests; however, starlings can also be pests themselves when they feed on fruit and sprouting crops. Common starlings may also be a nuisance through the noise and mess caused by their large urban roosts. Introduced populations in particular have been subjected to a range of controls, including culling, but these have had limited success except in preventing the colonisation of Western Australia. The species has declined in numbers in parts of northern and western Europe since the 1980s due to fewer grassland invertebrates being available as food for growing chicks. Despite this, its huge global population is not thought to be declining significantly, so the Common Starling is classified as being of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Distribution and habitat The global population of Common Starlings was estimated to be 310 million individuals in 2004, occupying a total area of 8,870,000 km2. Widespread throughout the Northern Hemisphere, the bird is native to Eurasia and is found throughout Europe, northern Africa (from Morocco to Egypt), India (mainly in the north but regularly extending further south and extending into the Maldives) Nepal, the Middle East including Syria, Iran, and Iraq and north-western China. Common starlings in the south and west of Europe and south of latitude 40°N are mainly resident, although other populations migrate from regions where the winter is harsh, the ground frozen and food scarce. Large numbers of birds from northern Europe, Russia and Ukraine migrate south westwards or south eastwards. In the autumn, when immigrants are arriving from eastern Europe, many of Britain's Common Starlings are setting off for Iberia and North Africa. Other groups of birds are in passage across the country and the pathways of these different streams of bird may cross. Of the 15,000 birds ringed as nestlings in Merseyside, England, individuals have been recovered at various times of year as far afield as Norway, Sweden, Finland, Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Germany and the Low Countries. Small numbers of Common Starling have sporadically been observed in Japan and Hong Kong but it is unclear from where these birds originated. In North America, northern populations have developed a migration pattern, vacating much of Canada in winter. Birds in the east of the country move southwards, and those from further west winter in the southwest of the US. Common starlings prefer urban or suburban areas where artificial structures and trees provide adequate nesting and roosting sites. Reedbeds are also favoured for roosting and the birds commonly feed in grassy areas such as farmland, grazing pastures, playing fields, golf courses and airfields where short grass makes foraging easy. They occasionally inhabit open forests and woodlands and are sometimes found in shrubby areas such as Australian heathland. Common starlings rarely inhabit dense, wet forests (i.e. rainforests or wet sclerophyll forests) but are found in coastal areas, where they nest and roost on cliffs and forage amongst seaweed. Their ability to adapt to a large variety of habitats has allowed them to disperse and establish themselves in diverse locations around the world resulting in a habitat range from coastal wetlands to alpine forests, from sea cliffs to mountain ranges 1,900 m above sea level.   Range map from www.oiseaux.net - Ornithological Portal Oiseaux.net

www.oiseaux.net is one of those MUST visit pages if you're in to bird watching. You can find just about everything there

Introduced populations The Common Starling has been introduced to and has successfully established itself in New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, North America, Fiji and several Caribbean islands. As a result, it has also been able to migrate to Thailand, Southeast Asia and New Guinea. South America Five individuals conveyed on a ship from England alighted near Lago de Maracaibo in Venezuela in November 1949, but subsequently vanished. In 1987, a small population of Common Starlings was observed nesting in gardens in the city of Buenos Aires. Since then, despite some initial attempts at eradication, the bird has been expanding its breeding range at an average rate of 7.5 km per year, keeping within 30 km of the Atlantic coast. In Argentina, the species makes use of a variety of natural and man-made nesting sites, particularly Woodpecker holes. Australia The Common Starling was introduced to Australia to consume insect pests of farm crops. Early settlers looked forward to their arrival, believing that Common Starlings were also important for the pollination of flax, a major agricultural product. Nest-boxes for the newly released birds were placed on farms and near crops. The Common Starling was introduced to Melbourne in 1857 and Sydney two decades later. By the 1880s, established populations were present in the southeast of the country thanks to the work of acclimatisation committees. By the 1920s, Common Starlings were widespread throughout Victoria, Queensland and New South Wales, but by then they were considered to be pests. Although Common Starlings were first sighted in Albany, Western Australia in 1917, they have been largely prevented from spreading to the state. The wide and arid Nullarbor Plain provides a natural barrier and control measures have been adopted that have killed 55,000 birds over three decades. The Common Starling has also colonised Lord Howe Island and Norfolk Island. New Zealand The early settlers in New Zealand cleared the bush and found their newly planted crops were invaded by hordes of caterpillars and other insects deprived of their previous food sources. Native birds were not habituated to living in close proximity to man so the Common Starling was introduced from Europe along with the House Sparrow to control the pests. It was first brought over in 1862 by the Nelson Acclimatisation Society and other introductions followed. The birds soon became established and are now found all over the country including the subtropical Kermadec Islands to the north and the equally distant Macquarie Island far to the south. North America After two failed attempts, about 60 Common Starlings were released in 1890 into New York's Central Park by Eugene Schieffelin. He was president of the American Acclimatization Society, which tried to introduce every bird species mentioned in the works of William Shakespeare into North America. About the same date, the Portland Song Bird Club released 35 pairs of Common Starlings in Portland, Oregon. These birds became established but disappeared around 1902. Common starlings reappeared in the Pacific Northwest in the mid-1940s and these birds were probably descendants of the 1890 Central Park introduction. The original 60 birds have since swelled in number to 150 million, occupying an area extending from southern Canada and Alaska to Central America. Polynesia The Common Starling appears to have arrived in Fiji in 1925 on Ono-i-lau and Vatoa islands. It may have colonised from New Zealand via Raoul in the Kermadec Islands where it is abundant, that group being roughly equidistant between New Zealand and Fiji. Its spread in Fiji has been limited, and there are doubts about the population's viability. Tonga was colonised at about the same date and the birds there have been slowly spreading north through the group. South Africa In South Africa, the Common Starling was introduced in 1897 by Cecil Rhodes. It spread slowly and by 1954 had reached Clanwilliam and Port Elizabeth. It is now common in the southern Cape region, thinning out northwards to the Johannesburg area. It is present in the Western Cape, the Eastern Cape and the Free State provinces of South Africa and lowland Lesotho, with occasional sightings in KwaZulu-Natal, Gauteng and around the town of Oranjemund in Namibia. In Southern Africa populations appear to be resident and the bird is very much associated with man, his habitations and pastures. It favours irrigated land and is absent from regions where the ground is baked so dry that it cannot probe for insects. It may compete with native birds for crevice nesting sites but the indigenous species are probably more disadvantaged by destruction of their natural habitat than they are by inter-specific competition. It breeds from September to December and outside the breeding season may congregate in large flocks, often roosting in reedbeds. It is the most common bird species in urban and agricultural areas. West Indies The Common Starling was introduced to Jamaica in 1903, and the Bahamas and Cuba were colonised naturally from the US. This bird is fairly common but local in Jamaica, Grand Bahama and Bimini, and is rare in the rest of the Bahamas, eastern Cuba, the Cayman Islands, Puerto Rico and St. Croix.   By MPF - Self-made. References: native range, Snow & Perrins BWP Concise, del Hoyo et al.

Handbook of the Birds of the World 14: 724, and Harrison, Atlas of the Birds of the Western Palaearctic; introduced range, Sibley North American Bird Guide, Australia, South Africa, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2711671 Description The Common Starling is 19–23 cm long, with a wingspan of 31–44 cm and a weight of 58–101 g. Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 11.8 to 13.8 cm, the tail is 5.8 to 6.8 cm, the culmen is 2.5 to 3.2 cm and the tarsus is 2.7 to 3.2 cm. The plumage is iridescent black, glossed purple or green, and spangled with white, especially in winter. The underparts of adult male Common Starlings are less spotted than those of adult females at a given time of year. The throat feathers of males are long and loose and are used in display while those of females are smaller and more pointed. The legs are stout and pinkish- or greyish-red. The bill is narrow and conical with a sharp tip; in the winter it is brownish-black but in summer, females have lemon yellow beaks while males have yellow bills with blue-grey bases. Moulting occurs once a year- in late summer after the breeding season has finished; the fresh feathers are prominently tipped white (breast feathers) or buff (wing and back feathers), which gives the bird a speckled appearance.  Juvenile moulting in to adult winter plumage

Southport Pier, United Kingdom - August 2018

The reduction in the spotting in the breeding season is achieved through the white feather tips largely wearing off. Juveniles are grey-brown and by their first winter resemble adults though often retaining some brown juvenile feathering, especially on the head. They can usually be sexed by the colour of the irises, rich brown in males, mouse-brown or grey in females. Estimating the contrast between an iris and the central always-dark pupil is 97% accurate in determining sex, rising to 98% if the length of the throat feathers is also considered. The Common Starling is mid-sized by both starling standards and passerine standards. It is readily distinguished from other mid-sized passerines, such as thrushes, icterids or small Corvids, by its relatively short tail, sharp, blade-like bill, round-bellied shape and strong, sizeable (and rufous-coloured) legs. In flight, its strongly pointed wings and dark colouration are distinctive, while on the ground its strange, somewhat waddling gait is also characteristic. The colouring and build usually distinguish this bird from other starlings, although the closely related spotless starling may be physically distinguished by the lack of iridescent spots in adult breeding plumage. Like most terrestrial starlings the Common Starling moves by walking or running, rather than hopping. Their flight is quite strong and direct; their triangular-shaped wings beat very rapidly, and periodically the birds glide for a short way without losing much height before resuming powered flight. When in a flock, the birds take off almost simultaneously, wheel and turn in unison, form a compact mass or trail off into a wispy stream, bunch up again and land in a coordinated fashion. Common starling on migration can fly at 60–80 km/h and cover up to 1,000–1,500 km.  S. v. porphyronotus

By Catalogue of the Birds in the British Museum. Volume 13,

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11059937 Several terrestrial starlings, including those in the genus Sturnus, have adaptations of the skull and muscles that help with feeding by probing. This adaptation is most strongly developed in the Common Starling (along with the spotless and white-cheeked starlings), where the protractor muscles responsible for opening the jaw are enlarged and the skull is narrow, allowing the eye to be moved forward to peer down the length of the bill. This technique involves inserting the bill into the ground and opening it as a way of searching for hidden food items. Common starlings have the physical traits that enable them to use this feeding technique, which has undoubtedly helped the species spread far and wide. In Iberia, the western Mediterranean and northwest Africa, the Common Starling may be confused with the closely related spotless starling, the plumage of which, as its name implies, has a more uniform colour. At close range it can be seen that the latter has longer throat feathers, a fact particularly noticeable when it sings. Vocalization The Common Starling is a noisy bird. Its song consists of a wide variety of both melodic and mechanical-sounding noises as part of a ritual succession of sounds. The male is the main songster and engages in bouts of song lasting for a minute or more. Each of these typically includes four varieties of song type, which follow each other in a regular order without pause. The bout starts with a series of pure-tone whistles and these are followed by the main part of the song, a number of variable sequences that often incorporate snatches of song mimicked from other species of bird and various naturally occurring or man-made noises. The structure and simplicity of the sound mimicked is of greater importance than the frequency with which it occurs. In some instances, a wild starling has been observed to mimic a sound it has heard only once. Each sound clip is repeated several times before the bird moves on to the next. After this variable section comes a number of types of repeated clicks followed by a final burst of high-frequency song, again formed of several types. Each bird has its own repertoire with more proficient birds having a range of up to 35 variable song types and as many as 14 types of clicks. Males sing constantly as the breeding period approaches and perform less often once pairs have bonded. In the presence of a female, a male sometimes flies to his nest and sings from the entrance, apparently attempting to entice the female in. Listen to the Common Starling

Sound from www.xeno-canto.org

Sound from www.xeno-canto.org

Sound from www.xeno-canto.org

Older birds tend to have a wider repertoire than younger ones. Those males that engage in longer bouts of singing and that have wider repertoires attract mates earlier and have greater reproductive success than others. Females appear to prefer mates with more complex songs, perhaps because this indicates greater experience or longevity. Having a complex song is also useful in defending a territory and deterring less experienced males from encroaching. Singing also occurs outside the breeding season, taking place throughout the year apart from the moulting period. The songsters are more commonly male although females also sing on occasion. The function of such out-of-season song is poorly understood. Eleven other types of call have been described including a flock call, threat call, attack call, snarl call and copulation call. The alarm call is a harsh scream, and while foraging together Common Starlings squabble incessantly. They chatter while roosting and bathing, making a great deal of noise that can cause irritation to people living nearby. When a flock of Common Starlings is flying together, the synchronised movements of the birds' wings make a distinctive whooshing sound that can be heard hundreds of metres away. Listen to the Common Starling

Sound from www.xeno-canto.org

Sound from www.xeno-canto.org

Taxonomy and systematics The common starling was first described by Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae in 1758 under its current binomial name. Sturnus and vulgaris are derived from the Latin for "starling" and "common" respectively. The Old English staer, later stare, and the Latin sturnus are both derived from an unknown Indo-European root dating back to the second millennium BC. "Starling" was first recorded in the 11th century, when it referred to the juvenile of the species, but by the 16th century it had already largely supplanted "stare" to refer to birds of all ages. The older name is referenced in William Butler Yeats' poem "The Stare's Nest by My Window". The International Ornithological Congress' preferred English vernacular name is common starling. The starling family, Sturnidae, is an entirely Old World group apart from introductions elsewhere, with the greatest numbers of species in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. The genus Sturnus is polyphyletic and relationships between its members are not fully resolved. The closest relation of the common starling is the spotless starling. The non-migratory spotless starling may be descended from a population of ancestral S. vulgaris that survived in an Iberian refugium during an ice age retreat, and mitochondrial gene studies suggest that it could be considered as a subspecies of the common starling. There is more genetic variation between common starling populations than between nominate common starling and spotless starling. Although common starling remains are known from the Middle Pleistocene, part of the problem in resolving relationships in the Sturnidae is the paucity of the fossil record for the family as a whole. Subspecies There are several subspecies of the common starling, which vary clinally in size and the colour tone of the adult plumage. The gradual variation over geographic range and extensive intergradation means that acceptance of the various subspecies varies between authorities.  Click HERE for bigger table

Birds from Fair Isle, St Kilda and the Outer Hebrides are intermediate in size between S. v. zetlandicus and the nominate form, and their subspecies placement varies according to the authority. The dark juveniles typical of these island forms are occasionally found in mainland Scotland and elsewhere, indicating some gene flow from faroensis or zetlandicus, subspecies formerly considered to be isolated. Several other subspecies have been named, but are generally no longer considered valid. Most are intergrades that occur where the ranges of various subspecies meet. These include: S. v. ruthenus Menzbier, 1891 and S. v. jitkowi Buturlin, 1904, which are intergrades between vulgaris and poltaratskyi from western Russia; S. v. graecus Tschusi, 1905 and S. v. balcanicus Buturlin and Harms, 1909, intergrades between vulgaris and tauricus from the southern Balkans to central Ukraine and throughout Greece to the Bosporus; and S. v. heinrichi Stresemann, 1928, an intergrade between caucasicus and nobilior in northern Iran. S. v. persepolis Ticehurst, 1928 from southern Iran's (Fars Province) is very similar to S. v. vulgaris, and it is not clear whether it is a distinct resident population or simply migrants from southeastern Europe. Behaviour and ecology The common starling is a highly gregarious species, especially in autumn and winter. Although flock size is highly variable, huge, noisy flocks - murmurations - may form near roosts. These dense concentrations of birds are thought to be a defence against attacks by birds of prey such as peregrine falcons or Eurasian sparrowhawks. Flocks form a tight sphere-like formation in flight, frequently expanding and contracting and changing shape, seemingly without any sort of leader. Each common starling changes its course and speed as a result of the movement of its closest neighbours. Very large roosts, exceptionally up to 1.5 million birds, can form in city centres, woodlands or reedbeds, causing problems with their droppings. These may accumulate up to 30 cm deep, killing trees by their concentration of chemicals. In smaller amounts, the droppings act as a fertiliser, and therefore woodland managers may try to move roosts from one area of a wood to another to benefit from the soil enhancement and avoid large toxic deposits. Huge flocks of more than a million common starlings may be observed just before sunset in spring in southwestern Jutland, Denmark over the seaward marshlands of Tønder and Esbjerg municipalities between Tønder and Ribe. They gather in March until northern Scandinavian birds leave for their breeding ranges by mid-April. Their swarm behaviour creates complex shapes silhouetted against the sky, a phenomenon known locally as sort sol ("black sun"). Flocks of anything from five to fifty thousand common starlings form in areas of the UK just before sundown during mid-winter. These flocks are commonly called murmurations. Feeding The common starling is largely insectivorous and feeds on both pest and other arthropods. The food range includes spiders, crane flies, moths, mayflies, dragonflies, damsel flies, grasshoppers, earwigs, lacewings, caddisflies, flies, beetles, sawflies, bees, wasps and ants. Prey are consumed in both adult and larvae stages of development, and common starlings will also feed on earthworms, snails, small amphibians and lizards. While the consumption of invertebrates is necessary for successful breeding, common starlings are omnivorous and can also eat grains, seeds, fruits, nectar and food waste if the opportunity arises. The Sturnidae differ from most birds in that they cannot easily metabolise foods containing high levels of sucrose, although they can cope with other fruits such as grapes and cherries. The isolated Azores subspecies of the common starling eats the eggs of the endangered roseate tern. Measures are being introduced to reduce common starling populations by culling before the terns return to their breeding colonies in spring. There are several methods by which common starlings obtain their food but for the most part, they forage close to the ground, taking insects from the surface or just underneath. Generally, common starlings prefer foraging amongst short-cropped grasses and are often found among grazing animals or perched on their backs, where they will also feed on the mammal's external parasites. Large flocks may engage in a practice known as "roller-feeding", where the birds at the back of the flock continually fly to the front where the feeding opportunities are best. The larger the flock, the nearer individuals are to one another while foraging. Flocks often feed in one place for some time, and return to previous successfully foraged sites. There are three types of foraging behaviour observed in the common starling. "Probing" involves the bird plunging its beak into the ground randomly and repetitively until an insect has been found, and is often accompanied by bill gaping where the bird opens its beak in the soil to enlarge a hole. This behaviour, first described by Konrad Lorenz and given the German term zirkeln, is also used to create and widen holes in plastic garbage bags. It takes time for young common starlings to perfect this technique, and because of this the diet of young birds will often contain fewer insects. “Hawking” is the capture of flying insects directly from the air, and “lunging” is the less common technique of striking forward to catch a moving invertebrate on the ground. Earthworms are caught by pulling from soil. Common starlings that have periods without access to food, or have a reduction in the hours of light available for feeding, compensate by increasing their body mass by the deposition of fat.  Common Starling eats Chinese take away

Southport Pier, United Kingdom - August 2018

Nesting Unpaired males find a suitable cavity and begin to build nests in order to attract single females, often decorating the nest with ornaments such as flowers and fresh green material, which the female later disassembles upon accepting him as a mate. The amount of green material is not important, as long as some is present, but the presence of herbs in the decorative material appears to be significant in attracting a mate. The scent of plants such as yarrow acts as an olfactory attractant to females. The males sing throughout much of the construction and even more so when a female approaches his nest. Following copulation, the male and female continue to build the nest. Nests may be in any type of hole, common locations include inside hollowed trees, buildings, tree stumps and man-made nest-boxes. S. v. zetlandicus typically breeds in crevices and holes in cliffs, a habitat only rarely used by the nominate form. Nests are typically made out of straw, dry grass and twigs with an inner lining made up of feathers, wool and soft leaves. Construction usually takes four or five days and may continue through incubation. Common starlings are both monogamous and polygamous; although broods are generally brought up by one male and one female, occasionally the pair may have an extra helper. Pairs may be part of a colony, in which case several other nests may occupy the same or nearby trees. Males may mate with a second female while the first is still on the nest. The reproductive success of the bird is poorer in the second nest than it is in the primary nest and is better when the male remains monogamous. Breeding Breeding takes place during the spring and summer. Following copulation, the female lays eggs on a daily basis over a period of several days. If an egg is lost during this time, she will lay another to replace it. There are normally four or five eggs that are ovoid in shape and pale blue or occasionally white, and they commonly have a glossy appearance. The colour of the eggs seems to have evolved through the relatively good visibility of blue at low light levels. The egg size is 26.5–34.5 mm in length and 20.0–22.5 mm in maximum diameter.  Eggs, Collection Museum Wiesbaden, Germany

By Klaus Rassinger und Gerhard Cammerer, Museum Wiesbaden - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36755500 Incubation lasts thirteen days, although the last egg laid may take 24 hours longer than the first to hatch. Both parents share the responsibility of brooding the eggs, but the female spends more time incubating them than does the male, and is the only parent to do so at night when the male returns to the communal roost. The young are born blind and naked. They develop light fluffy down within seven days of hatching and can see within nine days. Once the chicks are able to regulate their body temperature, about six days after hatching, the adults largely cease removing droppings from the nest. Prior to that, the fouling would wet both the chicks' plumage and the nest material, thereby reducing their effectiveness as insulation and increasing the risk of chilling the hatchlings. Nestlings remain in the nest for three weeks, where they are fed continuously by both parents. Fledglings continue to be fed by their parents for another one or two weeks. A pair can raise up to three broods per year, frequently reusing and relining the same nest, although two broods is typical, or just one north of 48°N. Within two months, most juveniles will have moulted and gained their first basic plumage. They acquire their adult plumage the following year. As with other passerines, the nest is kept clean and the chicks' faecal sacs are removed by the adults. Intraspecific brood parasites are common in common starling nests. Female "floaters" (unpaired females during the breeding season) present in colonies often lay eggs in another pair's nest. Fledglings have also been reported to invade their own or neighbouring nests and evict a new brood. Common starling nests have a 48% to 79% rate of successful fledging, although only 20% of nestlings survive to breeding age; the adult survival rate is closer to 60%. The average life span is about 2–3 years, with a longevity record of 22 yr 11 m Predators and parasites A majority of starling predators are avian. The typical response of starling groups is to take flight, with a common sight being undulating flocks of starling flying high in quick and agile patterns. Their abilities in flight are seldom matched by birds of prey. Adult common starlings are hunted by hawks such as the northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) and Eurasian sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus), and falcons including the peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus), Eurasian hobby (Falco subbuteo) and common kestrel (Falco tinnunculus). Slower raptors like black and red kites (Milvus migrans & milvus), eastern imperial eagle (Aquila heliaca), common buzzard (Buteo buteo) and Australasian harrier (Circus approximans) tend to take the more easily caught fledglings or juveniles. While perched in groups by night, they can be vulnerable to owls, including the little owl (Athene noctua), long-eared owl (Asio otus), short-eared owl (Asio flammeus), barn owl (Tyto alba), tawny owl (Strix aluco) and Eurasian eagle-owl (Bubo bubo). More than twenty species of hawk, owl and falcon are known to occasionally predate feral starlings in North America, though the most regular predators of adults are likely to be urban-living Peregrine Falcons or Merlins (Falco columbarius). Common Mynas (Acridotheres tristis) sometimes evict eggs, nestlings and adult common starlings from their nests, and the lesser honeyguide (Indicator minor), a brood parasite, uses the common starling as a host. Starlings are more commonly the culprits rather than victims of nest eviction however, especially towards other starlings and Woodpeckers. Nests can be raided by animals capable of climbing to them, such as stoats (Mustela erminea), raccoons (Procyon lotor) and squirrels (Sciurus spp.), and cats may catch the unwary. Common starlings are hosts to a wide range of parasites. A survey of three hundred common starlings from six US states found that all had at least one type of parasite; 99% had external fleas, mites or ticks, and 95% carried internal parasites, mostly various types of worm. Blood-sucking species leave their host when it dies, but other external parasites stay on the corpse. A bird with a deformed bill was heavily infested with Mallophaga lice, presumably due to its inability to remove vermin. The hen flea (Ceratophyllus gallinae) is the most common flea in their nests. The small, pale house-sparrow flea C. fringillae, is also occasionally found there and probably arises from the habit of its main host of taking over the nests of other species. This flea does not occur in the US, even on House Sparrows. Lice include Menacanthus eurystemus, Brueelia nebulosa and Stumidoecus sturni. Other arthropod parasites include Ixodes ticks and mites such as Analgopsis passerinus, Boydaia stumi, Dermanyssus gallinae, Ornithonyssus bursa, O. sylviarum, Proctophyllodes species, Pteronyssoides truncatus and Trouessartia rosteri.  Dermanyssus gallinae, a parasite of the common starling

By AW - Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5,

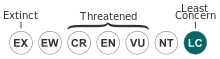

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6967126 The hen mite D. gallinae is itself preyed upon by the predatory mite Androlaelaps casalis. The presence of this control on numbers of the parasitic species may explain why birds are prepared to reuse old nests. Flying insects that parasitise common starlings include the louse-fly Omithomya nigricornis and the saprophagous fly Camus hemapterus. The latter species breaks off the feathers of its host and lives on the fats produced by growing plumage. Larvae of the moth Hofmannophila pseudospretella are nest scavengers, which feed on animal material such as faeces or dead nestlings. Protozoan blood parasites of the genus Haemoproteus have been found in common starlings, but a better known pest is the brilliant scarlet nematode Syngamus trachea. This worm moves from the lungs to the trachea and may cause its host to suffocate. In Britain, the rook and the common starling are the most infested wild birds. Other recorded internal parasites include the spiny-headed worm Prosthorhynchus transverses. Common starlings may contract avian tuberculosis, avian malaria and retrovirus-induced lymphomas. Captive starlings often accumulate excess iron in the liver, a condition that can be prevented by adding black tea-leaves to the food. Status The global population of the Common Starling is estimated to be more than 310 million individuals and its numbers are not thought to be declining significantly, so the bird is classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as being of least concern. It had shown a marked increase in numbers throughout Europe from the 19th century to around the 1950s and 60s. In about 1830, S. v. vulgaris expanded its range in the British Isles, spreading into Ireland and areas of Scotland where it had formerly been absent, although S. v. zetlandicus was already present in Shetland and the Outer Hebrides. The Common Starling has bred in northern Sweden from 1850 and in Iceland from 1935. The breeding range spread through southern France to northeastern Spain, and there were other range expansions particularly in Italy, Austria and Finland. It started breeding in Iberia in 1960, while the spotless starling's range had been expanding northward since the 1950s. The low rate of advance, about 4.7 km per year for both species, is due to the suboptimal mountain and woodland terrain. Expansion has since slowed even further due to direct competition between the two similar species where they overlap in southwestern France and northwestern Spain. Major declines in populations have been observed from 1980 onward in Sweden, Finland, northern Russia (Karelia) and the Baltic States, and smaller declines in much of the rest of northern and central Europe. The bird has been adversely affected in these areas by intensive agriculture, and in several countries it has been red-listed due to population declines of more than 50%. Numbers dwindled in the United Kingdom by more than 80% between 1966 and 2004; although populations in some areas such as Northern Ireland were stable or even increased, those in other areas, mainly England, declined even more sharply. The overall decline seems to be due to the low survival rate of young birds, which may be caused by changes in agricultural practices. The intensive farming methods used in northern Europe mean there is less pasture and meadow habitat available, and the supply of grassland invertebrates needed for the nestlings to thrive is correspondingly reduced. Conservation status

Least concern (IUCN 3.1)

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2.

International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sighted: 18 April 2019 (Date of first photo that I could use) Location: Skara  Common Starling / Stare - Skara - 18 April 2019

Common Starling / Stare - Naturum, Lake Hornborga /Hornborgasjön - 19 April 2019

Common Starling / Stare - Naturum, Lake Hornborga /Hornborgasjön - 19 April 2019

Common Starling / Stare - Bjuv - 28 September 2019

Common Starling / Stare - Bjuv - 28 September 2019

Common Starling / Stare - Bjuv - 28 September 2019

PLEASE! If I have made any mistakes identifying any bird, PLEASE let me know on my guestbook  You are visitor no.

To www.aladdin.st since December 2005

|

|